Rambler 88 and the humpback whale

written by François Chevalier

The profile of Rambler 88 is very original, featuring distinctive vertical topsides, a bezeled tumblehome on the upper topsides extending from the bowsprit all the way to the transom, and a pronounced rake in the mast and in the keel fin.

One might ask the relationship between an ultralight maxiyacht and a whale? Juan Kouyoumdjian did not fear to create a paradox here, and he often enjoys astonishing his clients. It turns out that the pectoral fins of marine mammals never stall. And there is nothing worse than having an unresponsive helm on a maxi yacht sailing at full speed amongst a crowd of other boats gathered at a start line or when close reaching on the crest of a wave. So Kouyoumdjian was inspired by the renowned properties of the humpback whale fins to design the rudders for his latest yacht, Rambler 88.

Still extracted from the "Rambler Launch" video at New England Boatworks

First, let us address the size of this 88ft boat, why not 100ft like the other supermaxis? Rambler 88's owner George David wanted to win races on a boat with a 6 metre draught. Kouyoumdjian could have designed a 100 footer, but to be competitive, he would have needed an extra metre in draught. So the project was settled at 88 feet.

Launched on December 10th of last year at the New England Boatworks in Portsmouth, RI, the new Rambler was designed, like her older namesakes, to break ocean records and win offshore races. Built in full carbonfiber, this "small" speed machine features the same characteristics than her latest competitors, like Comanche (VPLP and Guillaume Verdier design), which was launched three months earlier. Her forward stations, with a full bow and a hard chine reminiscent of the vaka (centre hulls) of ocean trimarans, are very sleek, probably more so than previous maxiyachts. This hard chine configuration also features a distinctive topside step to flare off sprays efficiently, instead of flooding the cockpit as in the Volvo Ocean 65s. This hard chine has the benefit of providing good buoyancy in the upper topsides, despite a narrow waterline. Rambler 88 implements this feature even further than Comanche, and as such is indeed a genuine development of Groupama 4, the winner of the previous Volvo Ocean Race. After the bow, the bilge is flat so as to favour planing, and rounds gradually.

body plan, sheer plan, half-breadth plan and deck layout of Rambler 88

The sheer plan emphasises the importance of the forward part of the hard chine which flares off sprays, as well as its sinuous shape. The waterlines in the half-breadth plan are practically rectilinear and very sleek. As in Comanche, the rear half is a skimming dish.

As in previous instances, Kouyoumdjian payed special attention to the keel area, which is positioned in a distinct concavity; This extends the reach of the bulb when the keel is fully canted. As in previous IMOCA Open 60s for the Vendée Globe, the rotation axis of the keel has a positive slope, around 3°, in order to generate a slight vertical lift when fully canted. Kouyoumdjian's team focused especially on the heeling behaviour to draw the lines of the boat: the hard chine is not straight, instead the central part is a slightly raised soft chine, in order to increase the lateral wetted area, all the while minimising waterline dissymmetry in heeling conditions.

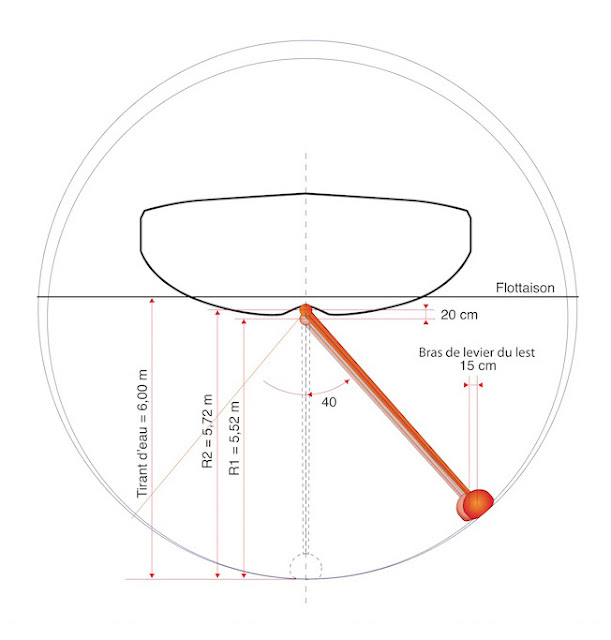

Keel rotation axis raised in a hull concavity

The keel rotation axis was raised by 20cm into a hull concavity and the keelfin was lengthened in the same amount. When the keel is canted 40°, the righting lever of the bulb benefits from an extra 15cm offset.

The daggerboards are of the same type as those of Comanche and of certain Volvo Open 70s. They have narrow terminations and a small bulb, reducing tip vortices and turbulent flowlines. They feature a slight inward slope and are kept out of line of the rudders.

Kouyoumdjian's team is highly specialised in sophisticated appendage design and surprised onlookers by producing shell-like rudders for Rambler 88. They were inspired by the pectoral fins of humpback whales to try to solve several problems which did not seem to have clear links between them. These huge flat-bottomed speed machines cannot be raced by autopilots, instead they require a unique racing approach, similar to that found in the Monte Carlo rally: In order to navigate faster between waves, the helm is often jolted violently, separating waterflow at the rudders, sometimes momentarily stalling them and disabling steerage. Also, twin rudders are capital on wide bodies, but the windward rudder often drags in the water at an unfavourable angle.

The proven efficiency of the humpback whale pectoral fins were tried on the rudder of the Icon 65, which donot stall when jolted

Particulars of Icon 65

rig: sloop

designer: Robert Perry

shipyard: Marten Yachts, NZ

year of launch: 2001

Length Over All: 20.04m (65ft 9in)

Load Waterline Length: 17.32m (56ft 10in)

Beam: 4.52m (14ft 10in)

Draught: 2.64m / 4.16m (8ft 8in / 13ft 8in)

Air draught: 27.90m (91ft 6in)

Displacement: 12.25 / 14 metric tonnes

Upwind sail area: 177sqm (1,905 sqft)

Downwind sail area: 450sqm (4,844 sqft)

IRC/TCC rating: 1,409

Studies of the humpback whale's renowned tubercular fins are not new, and those of Dr. Frank E. Fish, published in 1995, are authoritative. There have also been a few instances of rudders with protrusions mimicking the humpback's tubercles. According to Kevin Welch, the second owner of the Icon 65 designed by Bob Perry and launched in 2001, the helm had a tendency to stall when the boat was driven hard. This 20m (66ft) boat was designed with a removable interior for racing, as well as a dropkeel for shoal cruising. When Perry called upon performance specialist Paul Bieker to think about changing appendages, the latter picked up a 2008 paper published by the University of Harvard titled "How Bumps on Whale Flippers Delay Stall: An Aerodynamic Model". Written by Ernest van Nierop, Silas Alben and Michael Brenner, this paper was based on the results of wind tunnel tests as well as theoretical computations which proved that greater protrusions on the leading edge of a foil could delay stalling. Bieker designed a rudder with three of these tubercles in the upper section and Welch was delighted to note that the change had stopped the boat from stalling. It turned out that the pectoral fin was in fact an excellent "hydrodynamic model".

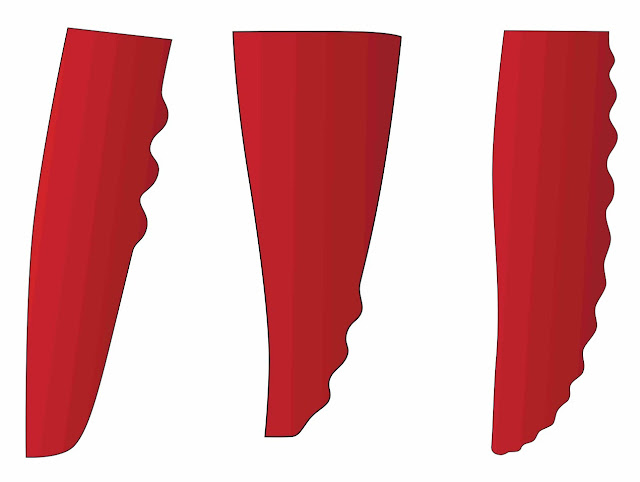

Rudder variations - left: Paul Bieker's rudder, destined to the Icon 65 - center: Juan Kouyoumdjian's rudder destined to Rambler 88, with three tubercles on the lower section - right: a rudder inspired directly from the humpback's anatomy

© François Chevalier 2015

Juan Kouyoumdjian favoured developing the tubercles on the lower sections of Rambler 88's rudders, where the steady flow along the three tubercles maintain the upper sections in steady flow also, thus increasing lift, whilst reducing the tip vortex effect. Furthermore, the submerged tubercular lower sections of the windward rudder, which is not inline with the heading, provides a 10% reduction in drag, as demonstrated by Dr. Fish. (see graphic and comments in part two)

Rambler 88's first outing took place during the Ft. Lauderdale to Key West Race last January. Sailing her first race in spinnaker weather with no sizeable competitors, she easily achieved line honours, completing the 160 nautical mile course with a small genoa in 11 hours 51 minutes with a 13.5kt average. She missed the first place on corrected time by a hair (5 thousandths of a knot), beaten by the Shaun Carkeek C40 Spookie, which arrived over four hours behind her.

Chart of the RORC Caribbean 600 race course - The monohull record soundly broken by Rambler 88 in 1 day 19 hours and 5 minutes, i.e. 12 hours ahead of the 100ft Finot/Conq Nomad IV

In the following month, George David's new maxi took the start line of the RORC Caribbean 600 race, held around the Leeward Islands. Rambler 88 took line honours in 1 day 19 hours and 5 minutes, breaking the standing monohull record held since 2011 by her namesake Rambler 100 by four hours. This time she raced with her complete set of sails, including a large bowsprit genoat and all spinnakers, which increased her IRC/TCC rating significantly. She took third place on corrected time, behind the mini maxi Bella Mente and the TP52 Scorcha.

The most exciting rendez-vous took place in the following month in the idyllic setting of the Voiles de Saint Barth, with race courses decided on the morning of each race to suit the weather forecast. The thrills came from Rambler 88's match with the 100ft scarecrow Comanche, owned by Jim Clark, designed by VPLP and Guillaume Verdier, and skippered by Ken Read. Though Comanche's extra 12ft provided higher speeds in all conditions, Juan Kouyoumdjian gave right to owner George David and skipper Brad Butterworth, who beat Comancheon corrected time on every occasion. George David said: "Of course, she was ahead of us on elapsed time and I admit that I was impressed by her speed". Richard Mille rewarded every crewmember of Rambler 88 with an RM 60-01 Regatta Flyback Chronograph timepiece, one of the most expensive production watches at the moment, estimated to retail at the same cost as a 40ft sailing boat...This wristwatch, with a battery life of a mere 55 hours does have the advantage of having a compass which point to North correctly in both hemispheres.

Kouyoumdjian has succeeded in delivering a faster boat than the 8-year old Rambler 100 in any condition. He has not spared compliments to the designers of Comanche who have "significantly raised the bar in the sailing game", and has returned to the drawingboard of an upcoming 100-footer project with 7m draught!

The name of the humpback whale species does not refer to its tubercular pectoral fins, or the protrusions around the jaws or on its head; The whale owes its name to its curving back above the surface when diving

Of all marine mammals, the humpack whale has always astonished onlookers with its jumping prowess. Despite weighing as much as 30 metric tonnes, these capable swimmers can achieve a maximum speed of 15kt, turn on the spot, breach completely, and spin on themselves.

Black in colour, with distinct white spots, every individual can be easily identified. The shape and colour of their pectoral fins are also unique identifiers. The fins themselves have been the subject of multiple biological studies, including that of Dr. Frank E. Fish and Juliann M. Battle, from the West Chester University of Pennsylvania, published in 1995, which remains the reference work. The detailed descriptions of the fins of a young 9-metre individual and the following hydrodynamic analyses published by aeronautical researchers have proven the exceptional qualities of this appendage, particular skilled in carrying out incredible moves for such a massive animal.

Description:

length: between 9 and 18 metres, 4 metres at birth

displacement: from 10 to 40 metric tonnes

diving breath: from 5 to 30 minutes

diving depth: down to 120 metres

lifespan: from 30 to 50 years

population: approximately 35 000 individuals, present in all oceans

diet: plankton and small fish

fishing technique: surfaced, mouth wide open or creating bubbles to resemble a school of fish, solitary or in groups.

pectoral fins: located in the first quarter or first third of the overall length, measuring from 2.5 to 6 metres in length, with distinctive tubercles on the leading edge

Humpack whale pectoral fin © François Chevalier 2015

If we section the fin from top to bottom, as Dr. Fish did, the shapes appear evidently irregular; None are the same. The curves on the leading edge vary randomly. However, it is possible to isolate these curves and to categorise them into a profile class. In turn, we can observe that a this section corresponds to a NACA 634-24 foil profile, as described in the reference work by Mssrs. Abbott & Dœnhoff, and that its curve provides the best lift coefficient for angles of attack in excess of 15°, whereas conventional rudder foils stall when the angle of attack exceeds 12° (The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NACA, was established in 1915, and carried out exhaustive classification of hydrodynamic and aerodynamic foil profiles in the 1930s, before being dissolved and transferred into NASA).

Humpack whale pectoral fin © François Chevalier 2015

By sectioning the external and internal surfaces of the fin studied by Dr. Fish, much as in a half-hull, we can observe that the lines are far from smooth or symmetrical in shape. The lower surface features a slight convex area on the after section. In fact, this appendage appears so misshapen that it breaks established laws of hydrodynamics. It would seem that this complexity is essential to achieve greater efficiency!

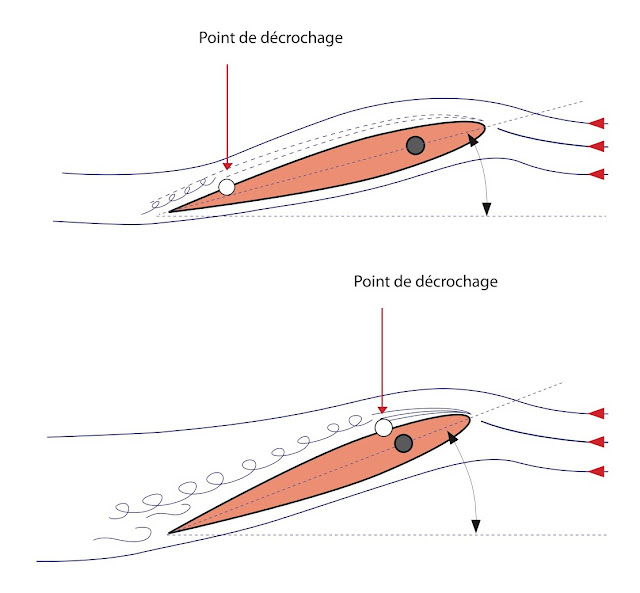

Flow separation at different angles of attack (top: steady flow, bottom: stalling)

Up to an angle of attack of 10°, the boundary layer is in steady flow, but the separation point moves gradually toward the leading edge. At approximately 12°, depending on speed, medium viscosity and surface state, the boundary layer separates at the leading edge, lift drops dramatically and the foil stalls.

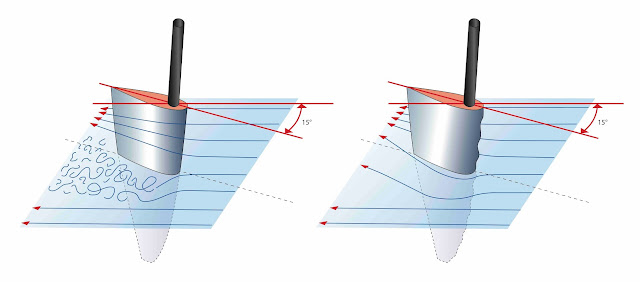

Laminar flow and turbulent flow

Measured at a given depth on a rudder with high angle of attack, the flowlines generate eddies on a conventional foil shape, but they remain linear and generate more lift on a foil that features protrusions.

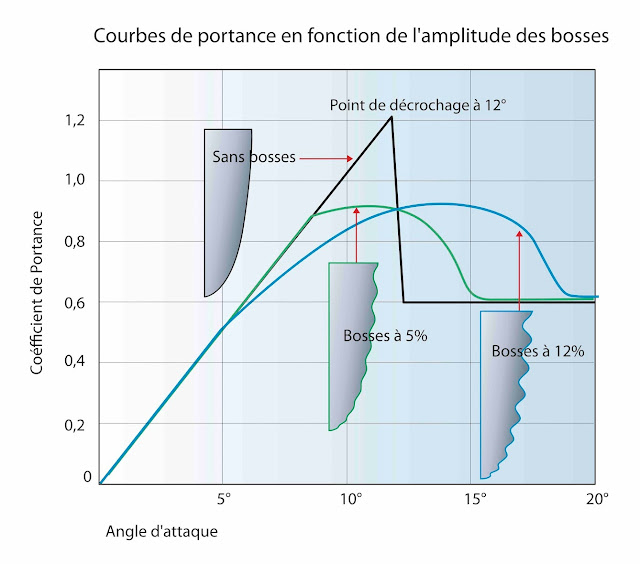

Lift curves according to protrusion amplitude - Lift coefficient/angle of attack

left: no protrusions (stalls at 12°) - middle: 5° protrusions - right: 12° protrusions

© François Chevalier 2015

The greater the protrusions, the later stalling is delayed. The conventional smooth foil stalls at 12°, whilst the foils that feature protrusions retain a normal curve without a threshhold limit.

Pressure on a NACA foil and on a foil with protrusions, with an angle of attack of 10°

left: loads - top: conventional NACA foil - bottom: flowlines close to surface of a foil with protrusions

© François Chevalier 2015

In 2001, Dr. Fish's University published a remarkable paper that he wrote in cooperation with Dr. Philip Watts, founder of Applied Fluids Engineering, Inc. The work included measurements of the tubercle effect on the leading edge of an airfoil with a 10° angle of attack. The work noted that the addition of protrusions provided a 4.8% increase of the lift coefficient and a drag reduction of 10.9%. The paper submits that flow deflection increases laminar flow and delays stalling.

|

|

George David driving Rambler 88 in the New York Yacht Club Annual Regatta, with Juan Kouyoumdjian onboard, and a good view of her soft chine amidships

After having read over all these works on the benefits of tubercle applications, should we not question why wind generators, aircraft and other similar airfoils or waterfoils should not be equipped with this particular feature? Certainly a few are thinking about it and the age of the sleek may come to an end sooner than we thought...

sailplans of Comanche, Rambler 88 and Perpetual Royal (formerly Rambler 100)

- Particulars:

Rambler 88

88ft maxi

rig: sloop

yacht designer: Juan Kouyoumdjian

shipyard: New England Boatworks, RI

launched: December 10th, 2014

Length of Hull: 27.00m (88ft 7in)

Load Waterline Length: 26.26m (86ft 2in)

beam: 7.10m (23ft 4in)

draught: 6.00m (19ft 8in)

air draught: 41.40m (135ft 10in)

bowsprit: 3.10m (10ft 2in)

displacement (lightship): 22 metric tonnes

ballast: 7.9 metric tonnes

mainsail area: 318 sqm (3,423 sq ft)

upwind sail area: 512/638 sqm (5,511/6,867 sq ft)

downwind sail area: 980 sqm (10,548 sq ft)

IRC/TCC rating: 1.88 (issued June 18th, 2015)

Comanche

100ft supermaxi

rig: sloop

yacht designer: VPLP & Guillaume Verdier

shipyard: Hodgdon Yachts, ME

christened: September 27th, 2015

Length of Hull: 30.48m (100ft)

Load Waterline Length: 30.25m (99ft 3in)

beam: 7.85m (25ft 9in)

draught: 6.67m (21ft 11in)

air draught: 45.75m (150ft 1in)

bowsprit: 3.70m (12 2in)

displacement: 29.5 metric tonnes

mainsail area: 410 sqm (4,413 sq ft)

upwind sail area: 760 sqm (8,181 sq ft)

maximum downwind sail area: 1400 sqm (15,069 sq ft)

IRC/TCC rating: 1.975 (issued June 16th, 2015)

Perpetual Loyal (formerly Rambler 100, originally Speedboat)

100ft supermaxi

rig: sloop

yacht designer: Juan Kouyoumdjian

shipyard: Cookson Boats, NZ

launched: April 17th, 2008

Length of Hull: 30.48m (100ft)

Load Waterline Length: 29.99m (98ft 5in)

beam: 7.35m (24ft 1in)

draught: 6.22m (20ft 5in)

air draught: 47.00m (154ft 2in)

bowsprit: 5.00m (16ft 5in)

displacement: 30.6 metric tonnes

ballast: 8 metric tonnes

mainsail area: 375 sqm (4,036 sq ft)

upwind sail area: 660sqm (7,104 sq ft)

maximum downwind sail area: 1,340 (14,423 sq ft)

IRC/TCC rating: 1.895

Merci à Donan Raven pour la traduction