IMOCA 2019

VPLP against GUILLAUME VERDIER

|

| ©F Chevalier Hugo Boss

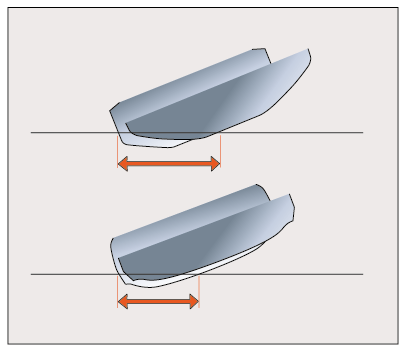

More stiffness, planning shapes, but more wetted surface.

|

It is still a little early to know which of the two IMOCAs is the fastest, Hugo Boss or Apivia. Who could have said during the last Vendée Globe that the next ones will fly. It was then a question of lightening the hull, reducing drag, even the architects said they didn't know if the foils brought more speed over a long distance. As a result, the first three were foil-fed, the second having lost its advantage by losing a foil. Then there was a second generation of foils, but the competitions were missing and those that took place were not conclusive. The first to really fly, Charal, gave us a great demonstration. Yes, he is flying! And it's off to a good start for them all to fly.

Bruno Troublé's first reaction when I told him that the first two monohulls launched for the America's Cup had totally different shapes, he simply replied that it didn't matter, they would be above the water! However, two teams of about twenty big heads have been working on the shapes of these hulls, because these sailboats fly, but also return or fall back into the liquid element.

|

| ©F Chevalier

Apivia

Less stiffness, round shapes, supported on a rail, little wetted surface.

|

The same will apply to IMOCAs, whether due to lack of wind or sea conditions. And even more, the 60' Open rule provides for two rudders, but their definition prohibits any winglet or carrier plane, and there is no question of giving them the slightest curve. "All leading and trailing edge points must be in the same plane." Too bad, a curvature would have arranged well the architects who are working on these sailboats that are missing a paste. However, there is no limitation in the gauge on the shape of the foils, which could take the shape of the small planes seen under the windsurfing boards, because the skipper flies with a very precarious balance, and his boat rears up to find a support point on the back of the hull between two flights.

It is more and more difficult to reconstruct a lines the best time to read the lines of these boats is during the rollover test session, and I didn't have the opportunity to go there for the last 6 IMOCA launched.

To simplify the study of the evolution of the design of these 60', I chose two sailboats that left the shipyard in August, Hugo Boss and Apivia. Several reasons for this choice, Alex Thomson's sailboat, a VPLP design, offers radical and original options, and Apivia is Guillaume Verdier's recent first plan. The fact that the previous winners were signed by VPLP / Guillaume Verdier seemed to me one more reason to analyse that it is the share of each of these architects in the success of the first two places since 2012, or at least which architectural options resulted from their competition.

Of course, the share of the skipper's preferences of each yacht in the general choices is also taken into account. Charlie Dalin is a trained naval architect and has followed Guillaume Verdier's Apivia design in every detail, he says, "I was at the heart of all the choices".

For his part, with his experience in the plans on which he has sailed, as varied as Marc Lombard, Juan Kouyoumdjian, Finot-Conq, Farr Yacht Design, and the duo VPLP / Guillaume Verdier, Alex Thompson has had time to get an idea of the sailboat that would finally allow him to win a Vendée Globe. His choice of VPLP, which had just designed the first IMOCA of the new generation for Charal, seems to be the logical continuation of his approach to obtain a sailboat that is as gliding as possible, with a reserve of power in the event of foil failure. His last experience, where he led a hell of a train until one of his foils encountered a floating object, made him want to protect himself from an overly radical option. Indeed, he had relied on his foils to obtain stiffness, by choosing a narrower sailboat with less drag. Also, the VPLP firm designed a powerful sailboat, with a beautiful width, 5.70 meters, a flat bottom that widens in planes parallel to the surface of the water at the list. and a bilge that starts from the bow just above the water and rises high on the transom. We find these flared shapes on the transom of the latest generations of TP52, these ultra sophisticated racing monohulls, a little heavier than the IMOCAs, displacing 7.5 tonnes for 15.85 metres in length. These flared plans allow the sailboat at the lodge to leave quickly for the planning. Faithful to his image as a destroyer of preconceived ideas, Alex went even further by refining the front axle, creating an even larger cut section than on the previous Hugo Boss. If the bottom of the bow is as flat and wide as possible, at the limit of the width allowed by the gauge, the bottom rises towards the bilge in the same inclined plane as at the stern. As Alex likes them, the shapes are cut with a knife, the sailboats have to fly or plane! The roof caught the attention of all those present at the first exit of the sailboat and was surprising in its length, original shape and colour. Actually, there's no cockpit, Alex is manoeuvring from the inside. All common manoeuvres open in the centre and are spread over four winches controlled by a column in the centre.

Above the winches, the screens display the data and monitor the outside with 360° cameras. A tiller allows you to steer without leaving the boat. The deckhouse extends to the mainsail listening rail and the sea water dives aft without filling the floor, which is reduced to a minimum. Knowing that the previous generation of 60' could take more than five hundred litres of seawater into their cockpit, Alex preferred to design an enclosed cockpit for manoeuvres and let the water and spray pass over it and remove obstacles so that they would not have the possibility to seal the sailboat's balance.

Hugo Boss

More stiffness, planning shapes, but more wetted surface.

Apivia

Less stiffness, round shapes, supported on a rail, little wetted surface.

|

|

| ©F Chevalier

Hugo Boss

Large flotation width at the heel, but planing shapes.

Apivia

Narrow and hollow-deep flotation based on its step.

|

One would have thought that the shapes of the new IMOCAs from VPLP and Guillaume Verdier would be at least from the same family. However, he has nothing to do with it. It even seems that there has never been such a difference between two IMOCAs released in the same month. Guillaume worked on the reduction of the wetted surface, a hull that hangs on a rail over the entire length of the sailboat, on the flow of sea water and spray, on the centre of gravity of the hull and rigging. He took particular care of the hull for the light airs and all the transition phases. The result is a narrow hull, barely 5.35 metres, with the maximum beam on the transom, from a bilge just above the waterline, a hollow cake, slightly pinched at the front, surrounded by a very marked step. The centre of gravity is far to the stern, even more so than in the VPLP plane. While the middle beam is well defended and has a large clear edge, with a rounded bilge and soft shapes, the deck is gutter-shaped from the front, until it reaches a depth of forty centimetres at mast level. As a result, the centre of gravity of the rigging has dropped accordingly. The only common point between Hugo Boss and Apivia, the bottoms on the back have a slight inflection point for "rocker", initiated by Juan Kouyoumdjian on Bernard Stam's Cheminée Poujoulat.

On both yachts, the choice of foils is as different as the hull shapes. Hugo Boss is equipped with large semi-circle shaped foils, while Aviva rests on a very wide U-shaped foil, the hollow of the U being parallel to the water at the heel, which gives it more stiffness. In flight, when the sailboats rest on their stern, Aviva landed on her spoiler, while Hugo Boss fell on the flat surface of her flank.

This study could have been accompanied by an analysis of Arkea-Paprec by Juan Kouyoumdjian, which is not lacking in originality. But it seems to us that this comparison is already quite tricky for the average person, and we reserve for ourselves an analysis of the four architects who have worked on the new IMOCAs, after the first new generation of foils, by the Vendée Globe.

Despite the frustration of architects, this class, which is the freest of all, is growing rapidly and its future is well secured if it can adapt to new challenges. Three particular points that could relaunch architectural research, the possibility of adding foils on the rudders, the one that blocks the width of the bow and the one that prevents the inflection points on the sections of the hull...